⭐ Walter Jerome Schloss – Quick Facts

The Humble Accountant Who Beat the Market

One afternoon in the late 1970s, a young analyst dropped by a nondescript Manhattan office with plywood bookshelves, an old filing cabinet, and a single man in shirtsleeves hunched over Value Line reports. Expecting a sophisticated Wall Street operation, the analyst was stunned to find a modest one-room office and an investor whose tools were a calculator, a pencil, and an unshakable belief in the power of cheap stocks. The man was Walter Schloss, and over the next few decades, he would deliver compound returns rivaling the most celebrated investors in history – without ever forecasting the economy, meeting management teams, or adopting modern portfolio theory.

Warren Buffett, who rarely dispenses praise lightly, once said of Schloss, “He knows how to identify securities that sell at considerably less than their value to a private owner: And that’s all he does. He owns many more stocks than I do and is far less interested in the underlying nature of the business. But he does not care what business it is. And he has made a fortune for himself and his clients.” It is a testament to Schloss’s legacy that his unpretentious, methodical approach remains one of the purest examples of deep-value investing ever practiced.

Want to think like the world’s best investors?

Dive into the mindsets, philosophies, and powerful quotes from legends like Soros, Fisher, Dalio, and more. Learn timeless strategies that turn insight into wealth – and transform how you see the markets.

From Graham’s Classroom to the Deep-Value Frontier

Walter Schloss was born in New York City in 1916, during a period when the stock market was still regarded as a speculative playground rather than an arena for disciplined analysis. Without a formal college education, Schloss began working as a runner on Wall Street at age 18. His career trajectory changed forever when he enrolled in Benjamin Graham’s investment course at the New York Stock Exchange Institute. Graham, widely regarded as the father of value investing, would become both mentor and inspiration.

After working at Graham-Newman Corporation (alongside another bright disciple, Warren Buffett) Schloss set up his own partnership in 1955. Unlike many of his contemporaries, he never sought publicity, preferring a quiet life of poring over balance sheets and annual reports. Schloss’s reputation was built entirely on results: over 47 years, he achieved compound annual returns of approximately 15% net of fees, outpacing the S&P 500 by several hundred basis points annually. His investing style was unambiguously deep value, relying on systematic screening of low-price-to-book stocks, wide diversification, and the unwavering conviction that cheapness was its own margin of safety.

The Schloss Philosophy: Simple, Systematic, Relentless

Walter Schloss’s core philosophy rested on a deceptively simple premise: buy stocks trading significantly below their tangible book value, hold them patiently, and sell when they approached fair value. This mechanical, price-driven approach was grounded in Graham’s teaching that the market is a voting machine in the short term but a weighing machine in the long run.

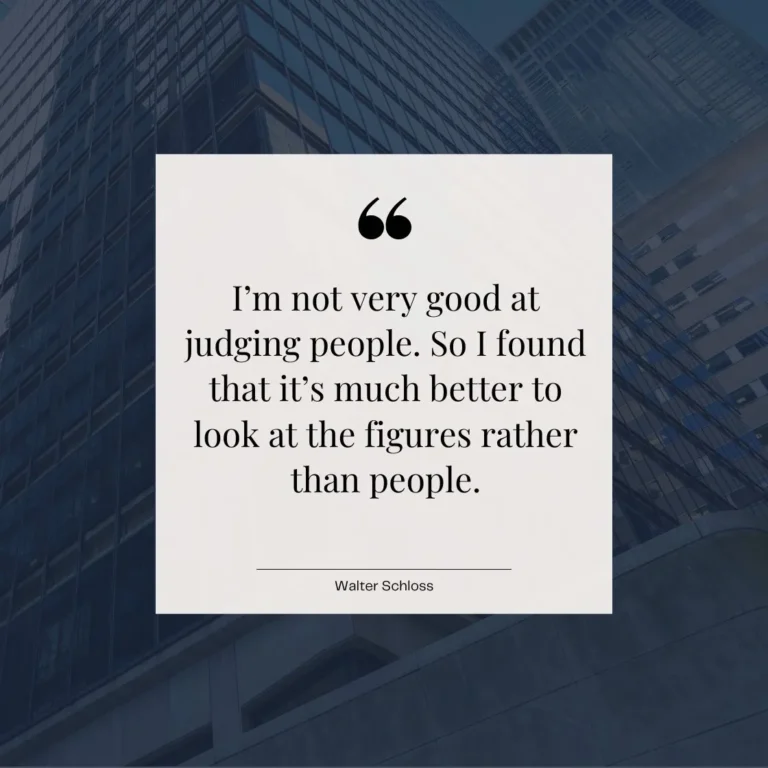

Schloss believed in what might be called “quantitative value investing.” Unlike Buffett, who evolved into a qualitative investor evaluating economic moats and durable competitive advantages, Schloss rarely concerned himself with management quality, future earnings power, or competitive dynamics. He looked for clear numerical signals—low price-to-book, low debt, history of paying dividends, insider ownership—and constructed a diversified portfolio of 100 or more positions. Each stock was a statistical bet that the market had mispriced its assets.

He summarized his method in a famous checklist:

- Price is the most important factor to use in relation to value.

- Try to establish the value of the company. Remember that a share of stock represents a part of a business.

- Use book value as a starting point.

- Have patience. Stocks don’t go up immediately.

- Diversify to protect yourself from mistakes.

- Buy on a scale down and sell on a scale up.

- Have the courage of your convictions.

In practical terms, Schloss would sort through Value Line and Moody’s manuals, flag companies trading at discounts of 30–50% to book, check the balance sheet to avoid severe distress, and buy incrementally. He accepted that many of his holdings would remain undervalued for long periods, but over time, mean reversion would close the gap between price and value.

Stories of the Reluctant Superstar

One of Schloss’s more instructive investments was in Cleveland Cliffs Iron Company in the late 1970s. At the time, the company traded well below book value, and most investors were pessimistic about iron ore prices. Schloss cared little for commodity cycles; he noted that the company held valuable assets that, even in liquidation, would likely exceed the stock’s market price. He quietly accumulated shares. Within a few years, rising iron ore prices and improving sentiment drove the stock price up nearly fivefold.

Schloss was also an early investor in Alleghany Corporation. Purchased when it was trading at about 60% of book value, the position multiplied several times as the company monetized its underappreciated assets and improved profitability. Unlike many contemporary investors, he never met management or conducted site visits. The balance sheet, he argued, told him most of what he needed to know.

He was remarkably candid about his limitations and failures. Schloss often quipped, “I don’t like losing money,” but admitted that his large, diversified portfolio always had plenty of disappointments. His philosophy was that in a basket of 100 deeply undervalued stocks, the winners would more than offset the losers.

A particularly relevant example for CFA candidates relates to the notion of margin of safety, a foundational concept in the CFA curriculum’s Equity Valuation readings. Schloss’s process illustrates in vivid detail how disciplined buying below intrinsic value can create a cushion against errors in estimation, unforeseen macroeconomic shocks, or company-specific setbacks.

Practical Lessons for CFA Candidates and Professionals

Schloss’s career offers several lessons highly relevant to CFA candidates and finance professionals:

First, the discipline of focusing on what you can measure. CFA candidates spend hundreds of hours learning to analyze financial statements, calculate valuation multiples, and dissect balance sheets. Schloss proved that these tools, applied rigorously and unemotionally, can drive superior returns even without sophisticated forecasting.

Second, the power of a systematic process. In the CFA curriculum, you learn about behavioral finance and the dangers of overconfidence, herding, and loss aversion. Schloss’s mechanical approach – screening for value, buying in tranches, diversifying widely—was designed precisely to mitigate these psychological biases.

Third, the enduring relevance of margin of safety. Whether you are valuing distressed debt, emerging market equities, or venture capital investments, the concept of buying at a discount to intrinsic value is an anchor against uncertainty.

Fourth, humility in investing. Schloss openly acknowledged that he could not predict earnings or business trajectories with great accuracy. His edge was not superior insight but superior discipline.

Fifth, the recognition that different styles can coexist. Many candidates assume that Buffett’s evolved quality approach replaced Graham’s strict quantitative value investing. But Schloss demonstrates that classic deep value can still thrive, particularly in less efficient corners of the market such as small-cap equities and neglected industries.

Controversies and Debates

Critics have argued that Schloss’s approach (focusing almost exclusively on low price-to-book) became less effective over time as markets became more efficient and intangible assets grew in importance. Companies today often derive substantial value from intellectual property, network effects, or brand equity, none of which show up on the balance sheet. In an era dominated by capital-light, platform businesses, Schloss’s method can miss structurally advantaged companies trading at premium valuations.

Others point out that his style requires immense patience and emotional fortitude. Deep-value stocks can remain depressed for years, creating career risk for professional managers. There is also a debate about whether diversification across 100 or more positions dilutes the potential alpha from higher-conviction ideas.

Nonetheless, Schloss’s results over nearly half a century remain a powerful counterargument to the efficient market hypothesis. His career challenges the idea that only information-rich, thesis-driven approaches can outperform. Sometimes, systematic discipline applied to simple metrics can deliver extraordinary outcomes.

Further Reading and Resources

To explore Walter Schloss’s work and philosophy in greater depth, consider the following resources:

- “The Superinvestors of Graham-and-Doddsville” Warren Buffett’s famous 1984 essay profiling Schloss and other Graham disciples.

- Value Investing: A Balanced Approach by Martin Whitman, which discusses deep-value methodologies with reference to Schloss’s work.

- Old editions of the Value Line Investment Survey, which Schloss used extensively.

- Berkshire Hathaway shareholder letters, which often reference Schloss and his results.

- The Intelligent Investor by Benjamin Graham, which formed the theoretical foundation for Schloss’s entire career.

Keep Learning, Stay Humble

Walter Schloss never sought fame, never managed billions, and never wavered in his belief that simple arithmetic and patience could beat the market. His career stands as a reminder that you don’t need charisma, complex models, or insider access to build enduring wealth. You need discipline, humility, and the courage to trust your process – even when it looks old-fashioned.

As you advance through the CFA journey, remember that mastery of fundamentals can be more powerful than any shortcut or trend. Keep studying. Keep questioning. And perhaps most importantly, keep your investing style true to who you are. That is how you build a career (and a life) in finance that stands the test of time.