What is a Hedge Fund of Funds?

A hedge fund of funds (FoF) is exactly what it sounds like: a fund that doesn’t invest directly in securities, but instead allocates capital across a portfolio of hedge funds.

Instead of betting on one manager, investors spread their risk across many.

In theory, this diversification was supposed to smooth returns, reduce risk, and offer access to elite hedge fund managers who would otherwise be unavailable to smaller investors.

But the theory didn’t always hold up.

Interested in Learning About Other Hedge Fund Strategies?

Why Fund of Funds Boomed

Throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, hedge fund of funds grew rapidly.

Wealthy individuals, pensions, endowments, and family offices all sought access to the supposedly magical alpha that hedge funds could deliver.

FoFs promised instant diversification across styles and strategies — long/short equity, global macro, event-driven, distressed credit — without requiring investors to pick winners themselves.

Plus, by pooling assets, FoFs claimed they could access top-tier managers who required high minimum investments.

It seemed like a perfect solution.

The Core Problems with Fund of Funds

While diversification was attractive, serious structural problems were baked into the FoF model — problems that became painfully obvious when returns faltered.

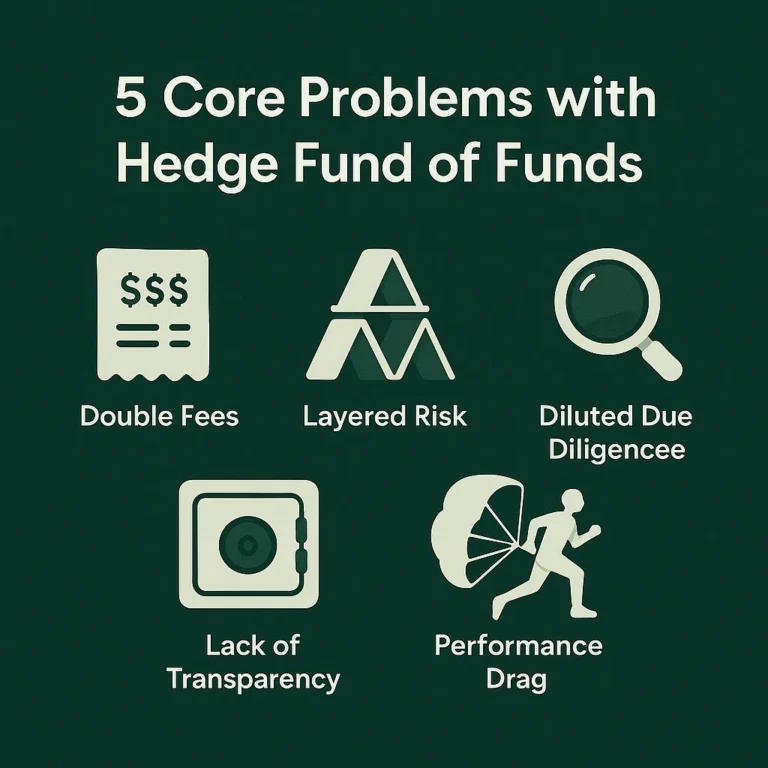

Double Fees (“Fees on Fees”)

The first major flaw: investors weren’t just paying hedge fund fees (the infamous “2 and 20” — 2% management fee and 20% performance fee).

They were also paying the FoF manager their own layer of fees — typically an additional 1% management fee and 10% performance fee.

This stacked fee burden often consumed a shocking share of gross returns, leaving little real alpha for the end investor.

Diluted Alpha and Duplication

While diversification can reduce idiosyncratic risk, too much diversification dilutes the very thing investors were seeking: outsized returns.

Many FoFs ended up holding dozens of hedge funds across similar strategies.

ather than assembling a complementary portfolio, they often duplicated exposure — especially to crowded trades — muting potential upside without truly mitigating risk.

Lack of Transparency

FoFs often couldn’t (or wouldn’t) tell their investors exactly which hedge funds they owned, citing confidentiality agreements.

That meant clients had little visibility into what they were actually invested in — including their risk concentrations, counterparty exposures, and liquidity profiles.

In some infamous cases (e.g., those exposed to Bernie Madoff through feeder funds like Fairfield Greenwich), this lack of transparency proved disastrous.

Amplification of Survivorship Bias

Hedge funds already suffer from survivorship bias: poorly performing funds shut down and disappear from performance databases, inflating reported industry returns.

By selecting funds based largely on past track records, FoFs amplified this bias even further, chasing managers who had performed well historically — without always recognizing the mean-reversion or risks embedded in those records.

Liquidity Mismatches

Many FoFs offered quarterly or even monthly liquidity to investors.

But the underlying hedge funds they invested in often had longer lockups or less frequent redemption periods.

In periods of market stress (like 2008), this mismatch became catastrophic, forcing FoFs to suspend redemptions and “gate” investors just when liquidity was needed most.

Case Studies and Examples

Several high-profile blowups highlighted these risks:

Fairfield Greenwich Group: Lost billions by allocating heavily to Bernie Madoff without proper due diligence.

Blackstone Strategic Alliance Fund: Even this giant faced challenges managing liquidity and performance drag during downturns.

Smaller FoFs: Many simply disappeared after 2008, unable to survive poor performance, high fees, and shattered investor trust.

By 2010, fund of funds — once considered essential — had become a dirty word in many institutional portfolios.

What Investors Should Know Today

Fund of funds still exist, but they are a much smaller part of the investment landscape.

Today’s FoFs must justify their value — often by offering access to highly specialized, niche strategies where individual investors truly cannot access managers otherwise.

Large institutional investors now prefer customized multi-manager platforms, direct hedge fund investments, or building their own diversified portfolios — without layering in another level of fees.

In short: the bar for FoFs is much, much higher.

Final Thoughts

The hedge fund of funds model promised easy diversification and elite access, but hidden fees, hidden risks, and diluted returns ultimately betrayed many investors

Today’s sophisticated allocators demand more: direct access, lower fees, and full transparency.

Diversification is good.

Paying twice for mediocre performance?

Not so much.

Key Takeaways

Hedge fund of funds once boomed but fell out of favor after 2008.

Double fees (“fees on fees”) crushed investor returns.

Transparency issues and liquidity mismatches amplified risks.

Investors today demand direct access and fee efficiency.