In 1992, one man famously “broke” the Bank of England, pocketing over $1 billion in profits in a single trade. That man was George Soros.

What did he understand better than anyone else? The currency peg.

Currency pegs are like tightropes strung over deep economic canyons. They offer stability and predictability, but the moment markets lose faith in their strength, the fall can be spectacular & devastating.

If you’ve ever wondered how abstract FX theory can translate into billion-dollar gains (or losses), the story of currency pegs and their dramatic collapses is your bridge. For CFA candidates and finance professionals, this goes beyond fascinating financial history into a living lesson in macroeconomics, risk management, and market psychology.

Let’s step beyond the textbooks to understand the allure, mechanics, and perils of currency pegs – and the Soros Effect.

Currency Pegs and the CFA Curriculum

Currency pegs, or fixed exchange rate regimes, are covered in the CFA Level II curriculum under Economics and Currency Exchange Rates. Here, candidates learn how governments anchor their currencies to another (often the U.S. dollar or euro) to stabilize trade, control inflation, or maintain investor confidence.

The theory seems elegant.

In practice, it’s messy.

Pegs can stabilize prices and encourage cross-border trade. But if markets suspect a peg is unsustainable, speculative attacks can force painful devaluations.

Understanding currency pegs isn’t only academic. It’s critical for evaluating sovereign credit risk, emerging markets exposure, and even portfolio construction.

Examples like currency crises in Asia and Latin America serve to illustrate how seemingly “stable” pegs can unravel with shocking speed.

How Currency Pegs Work, & Why They Break

Countries peg their currency for many reasons… reducing volatility, attracting foreign investment, or maintaining export competitiveness. For instance, Hong Kong has pegged its dollar to the U.S. dollar at around 7.8 HKD since 1983.

To maintain a peg, a central bank must intervene in currency markets. If the local currency is under pressure and wants to depreciate, the central bank must spend its foreign reserves buying its own currency to prop up its value.

Here’s the problem… reserves are finite.

And speculators know it.

If traders believe the central bank can’t defend the peg, they start selling the currency en masse. The pressure becomes self-fulfilling. The central bank eventually throws in the towel, devalues the currency, and chaos ensues.

This is precisely what George Soros exploited in 1992.

Currency pegs, or fixed exchange rate regimes, operate by committing a sovereign’s currency to trade at a predetermined rate relative to an anchor currency – commonly the U.S. dollar or euro. The mechanics rely on the monetary authority’s active intervention in the foreign exchange market to maintain that parity. This intervention involves buying or selling its own currency against reserves of the anchor currency. In effect, the central bank subordinates monetary policy to the exchange rate objective: interest rates, reserve management, and even capital controls are calibrated to defend the peg rather than to respond purely to domestic conditions.

The sustainability of a peg hinges on two pillars: the adequacy of foreign exchange reserves and the credibility of the regime. Adequate reserves allow the central bank to meet demand for conversion at the fixed rate, neutralizing speculative flows. Credibility, meanwhile, influences expectations; if market participants believe the peg will hold, speculative pressure is dampened. If doubts arise (often due to persistent current account deficits, capital flight, or policy inconsistency) self-fulfilling dynamics can emerge.

Traders short the domestic currency, forcing the central bank to intervene more aggressively. As reserves dwindle, defending the peg becomes increasingly costly, requiring ever-higher interest rates or fiscal contraction to stem outflows.

Breaks occur when the defending central bank either exhausts its reserves or deems the cost of defense (economic contraction, reserve depletion, loss of policy flexibility) unacceptable.

The shift from fixed to floating often manifests abruptly… a devaluation or abandonment of the peg triggers a step-function repricing of the currency. This repricing transmits through the balance of payments: liabilities denominated in foreign currency inflate in local terms, import prices spike, and inflationary pressures surge. The sudden adjustment, akin to a balance-of-payments crisis, frequently cascades into sovereign credit distress, banking crises, or broader macroeconomic dislocation.

Advanced analysis of peg sustainability incorporates metrics like reserve adequacy (import cover, short-term external debt ratios), real effective exchange rate misalignments, uncovered interest parity spreads, and forward market pricing.

Modern frameworks also consider political economy factors — fiscal discipline, institutional strength, and willingness to endure domestic pain to maintain parity.

The canonical lesson from historic breaks, from the ERM crisis to Thailand 1997, is that no peg is immune to speculative attack if the underlying fundamentals are inconsistent with the fixed rate.

Markets, when coordinated by clear arbitrage opportunities, possess balance sheets far larger than any single central bank.

The Soros Effect | Black Wednesday

The most iconic currency peg collapse belongs to the United Kingdom on September 16, 1992 (known as Black Wednesday).

Britain had joined the European Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM), committing to keep the pound within a narrow band relative to the Deutsche Mark. But Britain’s economy was weaker than Germany’s. High interest rates to support the pound were choking the UK’s recovery.

Soros sensed blood.

He bet billions that the Bank of England couldn’t hold the peg.

Traders piled in.

The Bank of England spent over £15 billion trying to defend the pound and raised interest rates twice in a single day.

But markets overwhelmed the central bank. Britain withdrew from the ERM and devalued the pound. Soros made roughly $1 billion in profit. The UK government’s credibility was shattered.

It was a lesson in how market forces can humble even large governments – and how currency pegs, once broken, leave deep economic scars.

Other Famous Peg Breaks

While Soros’ coup remains legendary, many other pegs have buckled under pressure…

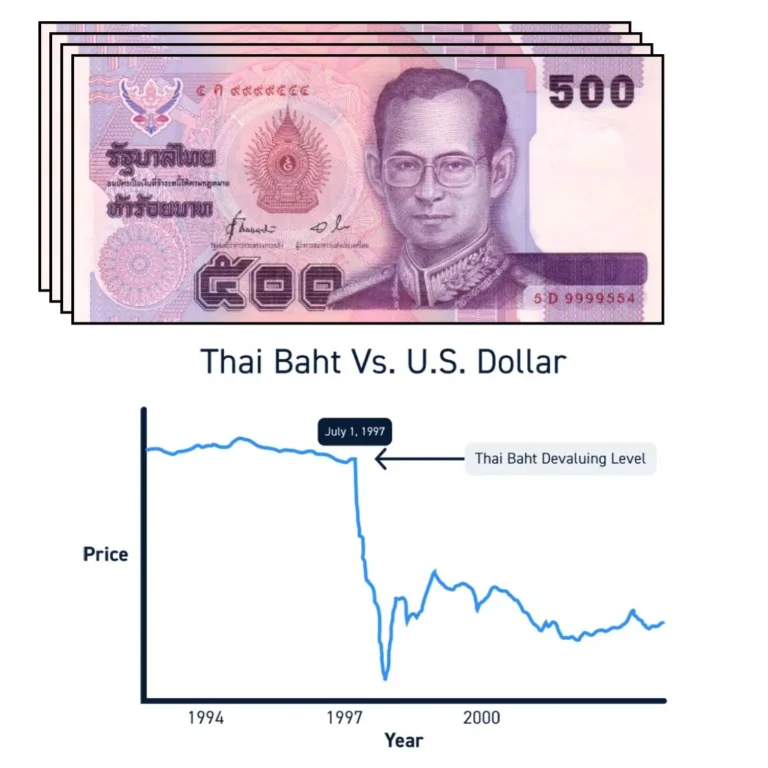

1997 Asian Financial Crisis: Thailand’s baht was pegged to the U.S. dollar. Mounting deficits and dwindling reserves forced Thailand to float the baht, triggering a domino collapse across Asia.

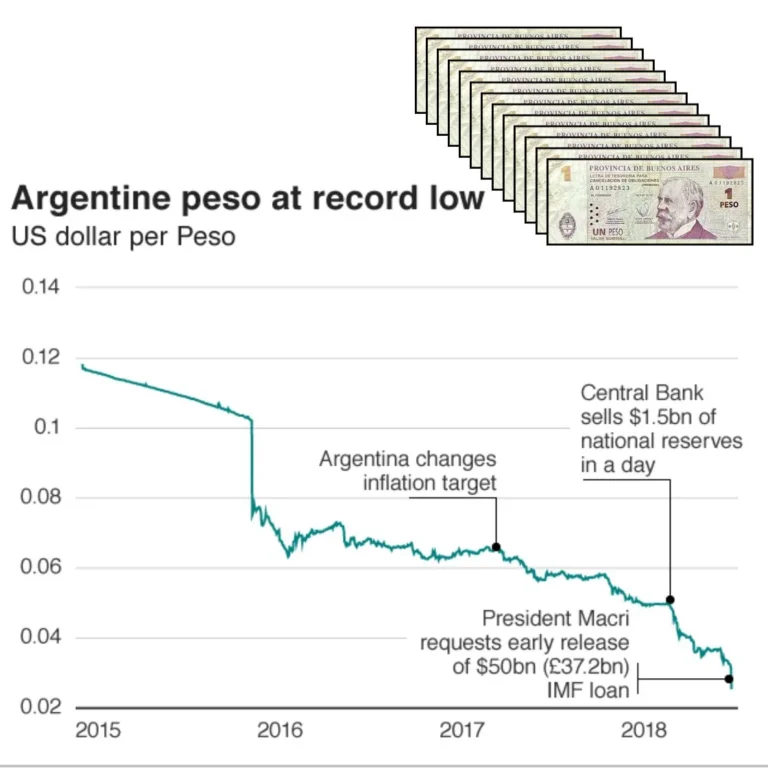

Argentina 2001: Argentina pegged the peso 1:1 to the dollar to fight hyperinflation. The economy stagnated. Eventually, reserves evaporated, the peg snapped, and the peso lost two-thirds of its value overnight.

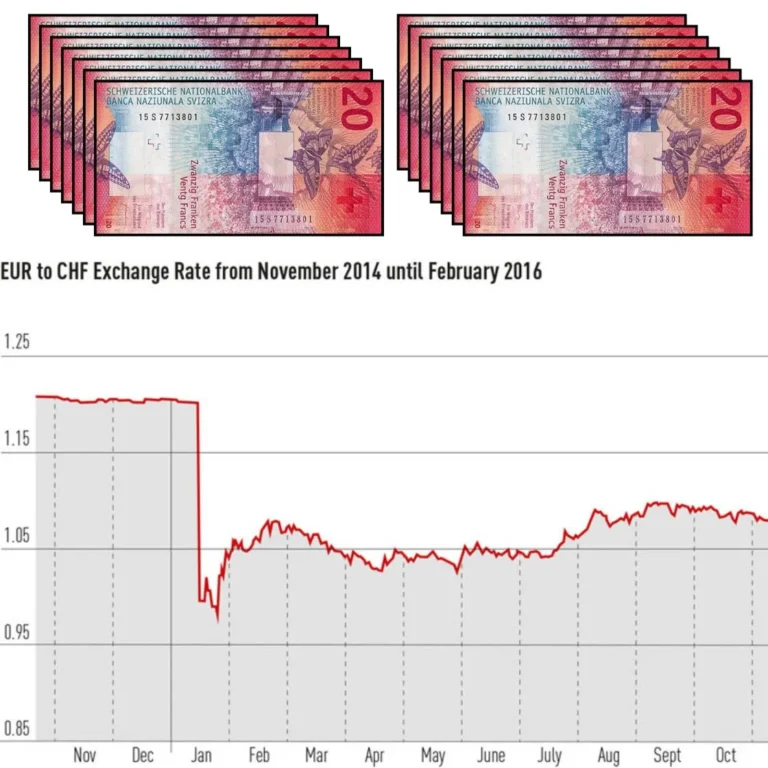

Swiss Franc 2015: The Swiss National Bank suddenly abandoned its 1.20 CHF/EUR floor. The franc soared over 30% in minutes. Many FX brokers went bankrupt as clients’ losses exceeded account balances.

Each of these events rattled global markets, obliterated wealth, and redefined geopolitical dynamics.

Pegs in the Modern Financial World

Currency pegs still exist today, though many are managed more flexibly. Hong Kong’s peg has endured decades of turmoil, supported by massive reserves and strict fiscal discipline. The Gulf States maintain dollar pegs to stabilize oil revenue streams and investment flows.

Yet even resilient pegs face challenges.

Rising U.S. interest rates can strain dollar-pegged currencies as capital seeks higher returns in the U.S. For emerging markets, defending a peg may require painful austerity or higher rates, potentially stalling economic growth.

For finance professionals, this means that pegs are both an anchor and a risk.

They provide clarity – until they don’t.

| IsoCode | Currency Name | Symbol | Position | Decimals | PeggTo | Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AED | Dirham (United Arab Emirates) | Dh | Right | 2 | USD | 3.67 |

| ATS | Schilling (Austria) | S | Right | 2 | EUR | 137.60 |

| BAM | Convertible Mark (Bosnia and Herzegovina) | KM | Right | 2 | EUR | 195.58 |

| BEF | Franc (Belgium) | BF | Left | 2 | EUR | 403.40 |

| BHD | Dinar (Bahrain) | BD | Right | 2 | USD | 0.38 |

| CYP | Pound (Cyprus) | £ | Right | 2 | EUR | 0.59 |

| DEM | Deutsch Mark (Germany) | DM | Right | 2 | EUR | 195.58 |

| DJF | Franc (Djibouti) | DF | Left | 2 | USD | 177.72 |

| ECS | Sucre (Ecuador) | Sucre | Right | 2 | USD | 25,000.00 |

| EEK | Kroon (Estonia) | Kr | Right | 2 | EUR | 1,564.664 |

| ERN | Nakfa (Eritrea) | Nfk | Right | 2 | USD | 15.00 |

| ESP | Peseta (Spain) | Ptas. | Right | 0 | EUR | 166.39 |

| FIM | Markka (Finland) | mk | Right | 2 | EUR | 594.57 |

| FRF | Franc (France) | F | Left | 2 | EUR | 655.96 |

| GIP | Pound (Gibraltar) | £ | Right | 2 | GBP | 1.00 |

| GRD | Drachma (Greece) | Dr | Right | 0 | EUR | 340.75 |

| IEP | Punt (Ireland) | Punt | Right | 2 | EUR | 0.79 |

| ITL | Lira (Italy) | Lit | Right | 0 | EUR | 1,936.27 |

| JOD | Dinar (Jordan) | JD | Right | 2 | USD | 0.71 |

| KYD | Dollar (Cayman Islands) | $ | Left | 2 | USD | 1.20 |

| LBP | Pound (Lebanon) | L£ | Right | 2 | USD | 1,507.50 |

| LSL | Loti (Lesotho) | L | Right | 2 | ZAR | 1.00 |

| LTL | Litas (Lithuania) | Litas | Right | 2 | EUR | 34.53 |

| LUF | Franc (Luxembourg) | LuxF | Left | 2 | EUR | 403.40 |

| LVL | Lat (Latvia) | Ls | Right | 2 | EUR | 0.70 |

| MTL | Lira (Malta) | £ | Right | 2 | EUR | 0.43 |

| NAD | Dollar (Namibia) | N$ | Left | 2 | ZAR | 1.00 |

| NLG | Guilder (Netherlands) | f. | Right | 2 | EUR | 220.37 |

| NPR | Rupee (Nepal) | NRs | Right | 2 | INR | 1.60 |

| OMR | Rial (Oman) | RO | Right | 2 | USD | 0.38 |

| PAB | Balboa (Panama) | B | Right | 2 | USD | 1.00 |

| PTE | Escudo (Portugal) | Esc | Right | 2 | EUR | 200.48 |

| QAR | Riyal (Qatar) | QR | Right | 2 | USD | 3.64 |

| SAR | Riyal (Saudi Arabia) | SR | Right | 2 | USD | 3.75 |

| SHP | Pound (Saint Helena) | £ | Right | 2 | GBP | 1.00 |

| SIT | Tolar (Slovenia) | SlT | Right | 2 | EUR | 239.64 |

| SKK | Koruna (Slovakia) | Sk | Right | 2 | EUR | 30.13 |

| SVC | Colon (El Salvador) | Colon | Right | 2 | USD | 8.75 |

| SZL | Lilangeni (Swaziland) | L | Right | 2 | ZAR | 1.00 |

| VEF | Bolivar (Venezuela) | Bs.F | Right | 2 | USD | 4.30 |

| XAF | CFA Franc (Central Africa) | F. | Right | 2 | EUR | 655.96 |

| XCD | Dollar (East Caribbean Dollar) | EC$ | Right | 2 | USD | 2.70 |

| XOF | SDR (Int. Monetary Fund) | F. | Right | 2 | EUR | 655.96 |

Currency Pegs in Financial Careers

So why should you, as a finance professional, care about currency pegs? Because they can influence nearly every facet of finance…

Asset Management – A sovereign credit analyst assessing an emerging market bond portfolio must gauge whether a currency peg is sustainable. A peg break can wipe out dollar-based returns.

Trading – Currency traders look for signs of stress in pegs as potential profit opportunities, or risks to hedge.

Corporate Finance – Multinationals must understand currency regimes when budgeting revenues, costs, and financing decisions in different markets.

Wealth Management – Advisers need to explain FX risks to clients, particularly when investing in emerging markets or foreign-denominated instruments.

Risk Management – Banks and investment firms stress-test their exposures to sudden currency shifts, especially in pegged regimes where complacency can breed hidden vulnerabilities.

In interviews, demonstrating an understanding of currency pegs can set you apart. Hiring managers may ask…

~ How would you spot signs that a peg is under pressure?

[Hint: signs of peg stress include a widening gap between forward rates and spot (implied devaluation), sharp reserve drawdowns, and emergency rate hikes far above the anchor currency. Rising sovereign CDS, FX option skews toward depreciation, and spikes in interbank rates also indicate strain. Persistent current account deficits, overvalued real effective exchange rates, and sudden capital flight amplify risk. Policy shifts like stealth band widening or unannounced interventions often precede collapse. When market pricing, macro fundamentals, and central bank behavior all point the same way, the peg’s credibility is failing and speculative pressure is near a tipping point.]

~ What indicators would you monitor for sustainability?

[Hint: key indicators include foreign reserve adequacy (relative to short‑term external debt, imports, and M2), real effective exchange rate misalignment, and current account balances. Monitor capital flow trends, sovereign CDS spreads, and forward/NDF pricing for early stress signals. Policy credibility matters like fiscal deficits, inflation differentials, and consistency of monetary policy with the anchor currency are critical. Sudden interest rate hikes or capital controls suggest fragility. Cross‑market cues like equity sell‑offs, bond spread widening, and liquidity stress all confirm mounting pressure. A sustainable peg shows ample reserves, credible policy alignment, and minimal forward‑market pricing of devaluation risk.]

~ How does a peg collapse affect local equity markets or bond spreads?

[Hint: a peg collapse typically triggers sharp local currency depreciation, eroding USD returns on equities and driving capital flight. Equity markets often sell off due to higher import costs, inflation spikes, and monetary tightening. Bond spreads widen dramatically as sovereign credit risk reprices… hard‑currency bonds reflect devaluation‑driven balance sheet stress, while local bonds face surging yields amid inflation and policy uncertainty. Foreign investors demand higher risk premia or exit entirely, deepening illiquidity. Recovery depends on post‑crisis policy response, credible reforms can stabilize spreads, but prolonged fiscal or banking distress often leads to sustained underperformance versus regional peers.]

If you can tie textbook knowledge to real-world events like Black Wednesday or the Swiss franc shock, you’ll appear knowledgeable & market-savvy.

Controversies and Debates

Currency pegs stir fierce debates among economists. Proponents argue pegs bring stability, especially for small economies reliant on trade. Critics counter that pegs often store up economic imbalances and lead to abrupt, painful adjustments.

There’s also the moral hazard problem… international institutions like the IMF sometimes bail out countries after peg failures, potentially encouraging risky behavior.

The political cost is high, too. Pegs often force governments to prioritize defending the currency over domestic economic growth, imposing austerity and social unrest.

Soros himself has been both lauded and vilified – praised for exposing economic imbalances, criticized for profiting from crises that left millions worse off.

Tips for CFA Candidates

Currency pegs appear in multiple CFA contexts, from Level II’s FX readings to portfolio management and sovereign risk analysis at Level III.

Here’s how to tackle the topic…

- Understand the mechanics of pegs – how central banks use reserves and interest rates to maintain a fixed rate.

- Remember that defending a peg drains foreign reserves. When reserves run out, the peg usually breaks.

- Study classic crises. The CFA exams love to test real examples like the Asian Financial Crisis or the Soros trade.

- Connect pegs to broader macro themes: current account deficits, inflationary pressures, capital flight.

Common mistakes candidates make include assuming pegs are “permanent” and underestimating how quickly sentiment shifts. Always ask yourself: “What happens if the peg breaks?”

Recommended Further Reading

To deepen your understanding beyond the CFA curriculum, consider:

- The Alchemy of Finance by George Soros – A fascinating read into Soros’ reflexivity theory and how he interprets markets.

- Currency Wars by James Rickards – Though somewhat sensationalist, it gives a dramatic overview of how FX battles shape geopolitics.

- World Bank – Choice of Exchange Rate, Regimes for Developing Countries

- International Monetary Fund – Exchange Rate Regimes in an Increasingly Integrated World Economy

- Bloomberg’s FX and Emerging Markets coverage – Essential for real-time insight into currency developments.

- Podcasts like Odd Lots or Macro Voices often dissect currency crises in engaging, practical ways.

Final Thoughts

Currency pegs are monuments to human ambition – a belief that governments can hold markets at bay. Sometimes they succeed for decades. Other times, a single determined speculator can topple them in days.

For CFA candidates and finance professionals, understanding currency pegs is more than passing an exam. It’s about recognizing the fragility beneath apparent stability. It’s about preparing for shocks, spotting opportunities, and staying vigilant when others grow complacent.

Because, as Soros proved, the market always has the final say.

And knowledge remains your strongest currency of all. Keep learning, stay curious – and never forget that in finance, nothing is truly fixed forever.