🔒 Download Supplementary Reading List to take your understanding to the next level

🔓 Download Terminology List covered in this video

Flashcards: Introduction to Digital Assets

Introduction to Digital Assets: A Comprehensive Guide for CFA Level I Candidates

Digital assets have rapidly emerged from niche curiosity to a significant component of modern finance. What exactly are digital assets, and why do they matter to today’s investors?

This long-form guide will delve into the foundations of digital assets, the technology behind them, the various types and investment vehicles, and their distinctive features, risks, and return characteristics.

Geared toward CFA Level I candidates (and any finance professional seeking a deep understanding), the discussion balances technical rigor with real-world examples and case studies. We’ll explore how blockchain and distributed ledger technology enable digital assets, examine cryptocurrencies, tokens, stablecoins, and more, and analyze how these assets compare to traditional investments in portfolios.

By the end, you should be equipped to describe financial applications of distributed ledger technology, explain the investment features of digital assets and contrast them with other asset classes, identify the forms of digital asset investments, and analyze the sources of risk, return, and diversification potential – all key learning outcomes in the CFA curriculum.

Let’s begin our journey into the evolving world of digital assets.

What Are Digital Assets?

Digital assets can be defined as cryptographically secured digital representations of value or rights recorded on a distributed ledger. In simpler terms, a digital asset is an electronic record (often on a blockchain) that confers ownership or usage rights and is secured by cryptography.

Unlike physical assets or traditional financial securities, digital assets exist purely in digital form on networked databases. A widely used definition comes from regulators like the UK Financial Conduct Authority, which describes a cryptoasset as “a cryptographically secured digital representation of value or contractual rights”.

These assets leverage cryptographic techniques (mathematical algorithms for securing information) to ensure that ownership cannot be counterfeited and transfers are verified.

Key characteristics that distinguish digital assets from traditional assets include:

(1) Intangibility – they have no physical form;

(2) Decentralization – many are created and managed without a central issuing authority, instead relying on distributed ledger technology;

(3) Programmability – they often have self-executing code (“smart contracts”) that imbue them with certain behaviors or rules; and

(4) Global transferability – ownership can be transferred near-instantaneously across borders via the internet, 24/7, without traditional banking intermediaries. In essence, digital assets are “programmable money or value”.

Examples of digital assets span a broad range.

The most well-known are cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin and Ether, which function as decentralized digital money.

Others include stablecoins (digital tokens pegged to fiat currencies or other assets), utility tokens (which provide access or usage rights within a blockchain platform, such as tokens used for decentralized applications), security tokens (digital representations of ownership in real assets or financial instruments, akin to digital shares or bonds), and non-fungible tokens (NFTs), which confer unique ownership of one-of-a-kind digital items (like digital art or collectibles).

We will explore these types in detail later, but it’s important to appreciate that digital assets come in various forms… currencies, tokens, asset-backed claims.

A Brief History and Evolution

The concept of digital assets has roots in decades of research on digital cash and cryptography, but the modern era began in 2009 with the launch of Bitcoin.

Bitcoin’s creator, known by the pseudonym Satoshi Nakamoto, introduced a revolutionary system of peer-to-peer electronic cash that for the first time solved the “double-spending” problem without a central authority.

Bitcoin’s debut marked the birth of blockchain-based currency and proved that decentralized digital value transfer was possible. In its early years, Bitcoin was used mainly by enthusiasts, and famously in May 2010 someone paid 10,000 BTC (then worth ~$40) for two pizzas – often cited as the first real-world Bitcoin transaction.

From that humble start, the digital asset landscape expanded rapidly. In 2015, Ethereum launched as a blockchain with a built-in programming language, enabling smart contracts and giving rise to a multitude of new tokens and decentralized applications. This unleashed waves of innovation: the initial coin offering (ICO) boom of 2017 saw startups issuing their own tokens (often representing project utility or investment-like claims) to raise billions of dollars in aggregate.

While many ICO projects failed (leading to a crash in 2018), the tokenization concept endured. By 2020–2021, the rise of decentralized finance (DeFi) platforms (for lending, trading, etc., without intermediaries) and the craze for NFTs (like the digital artwork by Beeple that sold for $69 million at Christie’s demonstrated new use cases and captivated public attention. The market capitalization of all crypto assets, which was practically zero in 2009, surged to around $3 trillion at its peak in late 2021 (see imf.org)

This growth has been accompanied by significant volatility and notable setbacks. For instance, in May 2022 the collapse of the TerraUSD stablecoin and its sister token Luna erased roughly $45 billion in market value within days, underscoring the extreme risks in parts of the crypto ecosystem. Later in 2022, the high-profile failure of the FTX exchange (due to alleged fraud and misused customer funds) shook investor confidence and prompted calls for stricter oversight.

Nonetheless, institutional adoption has continued: major companies have added crypto to their balance sheets, Bitcoin futures trade on regulated exchanges, and jurisdictions like the EU have rolled out comprehensive crypto regulations. By the end of 2023, an estimated 580 million people worldwide had used or owned cryptocurrency, and interest from both retail and institutional investors remains high.

Today, digital assets are firmly on the radar of finance professionals. The CFA Institute including an introduction to digital assets in its LOS reflects the recognition that these instruments are an important part of the alternative investments spectrum. In the next sections, we’ll examine the technological backbone that makes digital assets possible and then dive into the different categories of digital assets in detail.

Distributed Ledger Technology (DLT): The Backbone of Digital Assets

At the heart of nearly all digital assets is distributed ledger technology (DLT) – a new approach to record-keeping that replaces central authorities with decentralized networks. Understanding DLT is critical to grasping how digital assets function and why they have unique properties relative to traditional financial assets.

A distributed ledger is essentially a database spread across multiple computers or nodes that coordinate to verify and record transactions.

Each participant (node) has a synchronized copy of the ledger. Changes to the ledger (such as transfers of a digital asset) are validated collectively by the network rather than by a single central party. This architecture provides transparency (since all nodes see the same data), security through consensus (transactions must be agreed upon by the network, making unauthorized changes extremely difficult), and redundancy (no single point of failure, as copies exist on many machines).

The most famous type of DLT is the blockchain. A blockchain organizes data into blocks that are chained together using cryptographic hashes. Each block contains a batch of transactions and a reference (hash) to the previous block; this creates an immutable, chronological chain of records.

If anyone attempted to alter an earlier block, it would break the hash link and be rejected by the network. Thus, blockchains provide immutability – once data is recorded and confirmed, it cannot be altered without the consensus of the network. In Bitcoin’s blockchain, for example, transactions are grouped into blocks roughly every 10 minutes, and each block’s header includes a hash of the prior block’s header, ensuring tamper-resistance.

This innovation solved the double-spend problem by making it computationally infeasible to rewrite transaction history, thereby enabling trustless peer-to-peer value transfer.

Key features of DLT include: decentralization (no single controlling entity), consensus mechanisms (methods by which the network agrees on valid transactions), transparency (the ledger is visible to participants, especially in public blockchains), and security (cryptography secures the data and network). Let’s unpack a few of these concepts further:

Consensus Mechanisms: In lieu of a central authority, distributed ledgers rely on consensus algorithms to validate transactions and blocks. Different networks use different methods:

Proof of Work (PoW): Used by Bitcoin and others, PoW requires nodes (miners) to solve complex mathematical puzzles, expending computational energy, to propose the next block. It’s like a competitive lottery where winning is costly, ensuring miners have skin in the game. PoW is very secure but energy-intensive.

Proof of Stake (PoS): Used by newer networks (e.g., modern Ethereum after “the Merge”), PoS has validators stake their tokens to gain the right to validate blocks. The chance of being chosen to add a block often scales with the amount staked. This method is far more energy-efficient than PoW. There are many variations and other consensus models (delegated PoS, Proof of Authority, etc.), but all aim to achieve broad agreement without centralized control. The main point is that consensus mechanisms allow “trust without a central authority”– the network’s rules and incentives create security and trust in the data.

Public vs. Private Blockchains: Public blockchains (also called permissionless) are open networks that anyone can join and participate in the consensus process. Bitcoin and Ethereum are prime examples – any computer in the world can run the software and become a node or miner/validator. This openness maximizes decentralization and censorship-resistance. In contrast, private blockchains (permissioned) restrict access to a known group of participants (for example, a consortium of banks might maintain a private ledger for settlements). Private ledgers can be faster and ensure confidentiality, but they sacrifice the trust-minimized, open nature of public ones. They function more like a shared database among trusted parties. A useful analogy: public blockchains are like a global public bulletin board (anyone can write/read), whereas private blockchains are like an invite-only shared spreadsheet. Both use similar cryptographic techniques, but their governance and access differ. In summary, public = decentralized and open, private = controlled and limited accessj.

Nodes and Roles: In DLT networks, nodes are the computers that maintain copies of the ledger and help validate transactions. Some nodes are special – e.g., miners in PoW systems or validators in PoS – which propose blocks and secure the network. Other nodes might simply relay information or provide interfaces to users (wallet providers, explorers, etc.). The distributed nature means even if some nodes go offline or rogue, the network as a whole keeps functioning correctly, as long as a majority (or a required quorum) follow the rules.

Advantages and Limitations of DLT: By removing central intermediaries, DLT can increase efficiency and reduce costs in certain applications (for instance, potentially faster settlement of financial trades, as transactions can be final in minutes on a blockchain versus days in legacy systems). It also enhances security and trust – the immutable ledger can prevent fraud and simplify audits since records are transparent and cannot be doctored unnoticed. Additionally, DLT enables new models like decentralized finance and digital assets that wouldn’t be possible otherwise. However, there are trade-offs: public blockchains often face scalability challenges (Bitcoin and Ethereum have faced throughput bottlenecks and high fees during peak usage), and PoW systems consume a lot of energy by design. There are also legal and regulatory uncertainties – for example, if something goes wrong (a hack or bug), the lack of a central authority can make recourse difficult. Privacy is another concern: a fully transparent ledger is not ideal for all use cases (hence innovations in privacy coins and enterprise blockchains that hide transaction details).

It’s worth noting that DLT applications in finance extend beyond cryptocurrencies.

Banks and exchanges have experimented with using blockchain for tasks like clearance and settlement of securities, trade finance documentation, and interbank payments.

For instance, the Australian Securities Exchange (ASX) at one point planned (though later halted) a blockchain-based system to replace its settlement infrastructure.

Tokenization – the process of representing real-world assets (like real estate, commodities, or even fine art) as digital tokens on a ledger – is another promising application. It could enable fractional ownership and easier transfer of traditionally illiquid assets. Some central banks are developing central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) that use DLT-like technology to create digital versions of fiat currency. These examples underscore that beyond the hype of Bitcoin, the financial industry sees potential in DLT to increase transparency and efficiency in many domains.

In summary, distributed ledger technology underpins the entire digital asset ecosystem by providing a secure, decentralized way to track ownership and transfer of assets. Blockchain, as a specific implementation of DLT, introduced the breakthrough that powers cryptocurrencies and token networks today. Understanding these fundamentals will help us now explore the digital assets themselves – the “what” that rides on top of this technological “rails.”

Stablecoins

Stablecoins are digital assets designed to maintain a stable value, typically by pegging to a reference asset like the US dollar. They arose to combine the advantages of cryptocurrency (fast, borderless transactions on blockchain rails) with the stability of fiat money. The most common stablecoins are USD-pegged tokens such as Tether (USDT), USD Coin (USDC), and Binance USD (BUSD), which aim to remain at $1 value per token. These have become integral in the crypto trading ecosystem – providing a “cash” parking place for traders and a medium of exchange in decentralized finance.

Stablecoins achieve their peg through different mechanisms:

Fiat-collateralized stablecoins: These are backed 1:1 by reserves of the fiat currency or high-quality assets. For example, USDC is managed by a consortium that holds equivalent USD assets (cash, treasuries) for every coin issued. Users trust that they can redeem 1 USDC for $1 from the issuer. Regular audits or attestations are used to bolster confidence in reserves.

Crypto-collateralized stablecoins: These use cryptocurrency reserves to back the stablecoin. An example is DAI (from MakerDAO), which is generated by locking up volatile crypto (like Ether) as collateral in excess (e.g., $150 of ETH to issue $100 of DAI), with smart contracts managing the system. If collateral value falls too much, it gets sold to maintain the peg.

Algorithmic stablecoins: These attempt to hold value via algorithmic expansion and contraction of supply, often without full collateral. They use mechanisms akin to central bank monetary policy but in code (for instance, if price < $1, reduce supply; if > $1, increase supply). These designs have proven unstable in practice – the most infamous case being TerraUSD (UST), which lost its peg and imploded in 2022, wiping out tens of billions in value. Terra’s collapse highlighted the risks in algorithmic stablecoins: without robust collateral or a lender of last resort, confidence can evaporate quickly.

For CFA candidates, stablecoins are noteworthy because they blur the line between traditional and digital finance. They can be seen as digital money market instruments. However, they carry unique risks – like counterparty risk (one has to trust the issuer’s reserves are adequate and safe) and regulatory risk (many regulators are now scrutinizing stablecoins as they could impact financial stability).

For example, concerns have been raised about whether Tether truly has sufficient reserves, and some stablecoins have briefly broken their pegs during market stress. Still, when functioning, a stablecoin like USDC offers the convenience of crypto (programmable, 24/7 transfers) with minimal price fluctuation, making it very useful for trading and payments in the crypto ecosystem.

Tokens (Utility, Security, and More)

In blockchain terminology, a token usually refers to a digital asset that is built on top of an existing blockchain (as opposed to being the native currency of that blockchain).

For instance, Ethereum allows the creation of tokens via standards like ERC-20 (fungible tokens) and ERC-721 (non-fungible tokens). These tokens leverage Ethereum’s security and ledger, rather than having their own independent blockchain.

Utility Tokens: These tokens provide holders with some utility or access within a blockchain-based platform or service. They are akin to arcade tokens or software API keys.

For example, Filecoin (FIL) is a utility token used to access decentralized file storage on the Filecoin network – users pay in FIL to store data, and providers earn FIL for offering storage space. Another example is Basic Attention Token (BAT), used in the Brave browser ecosystem to reward users for viewing ads and to pay content creators.

The value of a utility token is linked to the adoption and usage of its underlying platform – essentially, it’s a user token for a specific network. These tokens are not meant to be general-purpose currencies, but rather have a specific role (though they trade freely on secondary markets, often attracting speculators).

Security Tokens: These are tokens that represent ownership of an investment product or asset – essentially, the digital asset is structured as a security and is subject to securities regulations. A security token could represent equity in a company (digitized shares), a bond or a share of a revenue stream, or ownership of a fraction of a real estate property, etc., recorded on a blockchain.

For instance, a real estate firm might tokenize a building such that each token represents a share in the rental income and value of the building. Security tokens promise to improve the efficiency of issuing and trading securities (24/7 markets, faster settlement, automated compliance via smart contracts).

They often come up in discussions of “tokenization of real assets.” While conceptually promising – making traditionally illiquid assets more liquid and accessible – the market is nascent due to regulatory complexities. Still, in 2019 the World Bank issued a tokenized bond, and various pilot projects have shown the feasibility of security tokens.

For exam purposes, remember that security tokens are simply digitized investment claims; legally, they are treated like stocks, bonds, or other securities, just with blockchain as the ledger. Their risks and rights are those of the underlying asset (plus some tech risk).

Governance Tokens: In decentralized platforms, especially DeFi protocols, governance tokens grant holders voting power on changes to the protocol’s rules or parameters.

For example, Uniswap’s UNI token allows holders to vote on proposals for the Uniswap decentralized exchange, such as fee structures or upgrades. These tokens are a bit like shareholder votes but in a decentralized context – they align with the concept of decentralized governance.

Their value often comes from the expectation that as the platform grows, governance tokens may eventually entitle holders to fees or have influence that the market values. They straddle the line between utility and security in some cases.

Other token types: The creativity is endless. Some tokens defy easy categorization or combine features. For instance, exchange tokens (like Binance’s BNB) started as utility tokens for exchange fee discounts but have taken on broader roles.

Meme tokens like Shiba Inu coin are community-driven and not attached to fundamental utility. Wrapped tokens represent an asset from another blockchain (e.g., Wrapped Bitcoin (WBTC) on Ethereum is an ERC-20 token fully backed by actual Bitcoin held in custody, allowing BTC to be used in Ethereum’s DeFi apps).

The takeaway: tokens are flexible digital assets representing all manner of value or rights. Tokenization is a powerful concept – virtually any asset or entitlement can be represented as a token, potentially improving transferability and transparency. We see experiments in tokenized carbon credits, supply chain tokens, loyalty points, and beyond.

Non-Fungible Tokens (NFTs)

Unlike cryptocurrencies or utility tokens which are fungible (one unit is interchangeable with another, like any one bitcoin is as good as any other), non-fungible tokens (NFTs) are unique digital assets.

An NFT is essentially a one-of-a-kind token that represents ownership or proof of authenticity of a specific item or piece of content. They gained massive popularity in 2021 for representing digital art and collectibles.

Each NFT has a distinct value and cannot be directly exchanged one-for-one with another NFT (just as you can’t swap two different paintings as equal, even if by the same artist).

NFTs often represent digital artworks, images, music files, videos, or even in-game items. The NFT is typically a token (often on Ethereum, using the ERC-721 standard) that contains metadata and a link or reference to the digital asset it represents.

Owning the NFT means you have a provable claim to owning the original item (even if copies of the image are everywhere, the blockchain verifies that you hold the “authentic” token for it). As Beeple’s $69 million NFT sale demonstrated, some collectors value this digital ownership highly. NFTs have also been used for things like virtual land in metaverse platforms, sports highlights (NBA Top Shot), domain names (Ethereum Name Service), and more.

From an investment perspective, NFTs are a very speculative and illiquid corner of digital assets. Their value is highly subjective – much like traditional art or collectibles – and can swing dramatically. They do highlight how digital assets aren’t only about currency or finance; they extend to culture and property rights in the digital realm.

NFTs also raise new questions: what exactly does one own (often, one owns the token pointing to the art, while the image itself might be hosted elsewhere, and copyright usually remains with the creator unless transferred)?

For CFA exam purposes, you should recognize that NFTs are unique tokens, mainly used for collectibles and rights to digital (or digitized physical) items.

Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs) and Other Digital Assets

Finally, a note on CBDCs: While not typically categorized with “crypto assets” since they are centrally issued, central bank digital currencies are worth mentioning.

A CBDC is a digital form of a country’s sovereign currency, issued by the central bank, potentially using DLT. For instance, China has piloted a digital yuan, and many other central banks are researching CBDCs.

The idea is to modernize currency with some benefits of crypto (fast electronic transfers, maybe programmability) while retaining central control and stability of fiat. If CBDCs roll out widely, they could coexist with or crowd out some private stablecoins.

However, CBDCs differ philosophically from cryptocurrencies: they are centralized and simply the digital evolution of fiat, whereas Bitcoin et al. are decentralized and a departure from the traditional system.

In summary, the universe of digital assets includes:

Decentralized cryptocurrencies (Bitcoin, Ether, etc.) functioning as new forms of money or commodity-like assets.

Stablecoins bridging crypto and fiat by maintaining steady value.

Tokens representing all sorts of utilities, rights, or assets (from accessing a network service to fractional real estate ownership).

Non-fungible tokens conferring ownership of unique digital items.

Emerging forms like CBDCs (state-backed digital cash).

This emerging asset class “combines technology and finance”, creating programmable assets and new investment possibilities.

It’s transforming concepts of ownership and value transfer.

Next, we’ll examine how these digital assets behave as investments – their features, risks, and where they might fit (or not fit) in portfolios.

Distinct Investment Features of Digital Assets

Digital assets, as investments, exhibit a set of features and behaviors that often differ markedly from stocks, bonds, or real estate.

As a CFA candidate, it’s crucial to analyze these characteristics – including valuation, volatility, liquidity, market efficiency, and correlation – to assess the role of digital assets in an investment context.

In this section, we’ll break down these features and contrast them with more traditional asset classes.

Valuation Challenges and the Absence of Cash Flows

One of the first questions an analyst might ask is: how do we value a digital asset?

For traditional assets, well-established valuation methods exist – equities can be valued via discounted cash flows or earnings multiples, bonds by present value of coupons, real estate by rental yields, etc.

Many digital assets lack intrinsic cash flows or clear fundamentals, making valuation an uncertain exercise. Cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin have no earnings, no dividends, and not even an industrial use – their value is based on supply and demand dynamics, scarcity, and network adoption. This means classical valuation models struggle to apply.

Various approaches have been attempted to gauge the “fair value” of cryptocurrencies:

Stock-to-Flow (S2F) Model: This model, borrowed from commodity analysis (often used for gold), looks at the stock of an asset (current supply) relative to flow (new supply per year). Bitcoin’s programmed supply schedule (halving its new issuance roughly every 4 years) means its stock-to-flow ratio increases over time. Some analysts have modeled Bitcoin’s price as proportional to its S2F, claiming it predicts higher prices as scarcity increases. The model had periods of seeming success but has been widely debated and criticized for lack of predictive power once the market matured.

Metcalfe’s Law and Network Value: Metcalfe’s Law posits that the value of a network is proportional to the square of the number of users (n²). For network-based assets like Bitcoin or Ethereum, one might estimate value by user growth or address usage. Indeed, some studies found that Bitcoin’s historical price correlates with the square of active addresses – suggesting a network effect valuation. However, capturing “users” or “activity” precisely is tricky, and multiple models (linear vs quadratic scaling) exist.

Relative Valuations and Utility Metrics: Investors also look at things like transaction volumes, fees generated on the network (for platforms like Ethereum, high fees might indicate high demand for block space), or macro analogies (e.g., comparing Bitcoin’s market cap to gold’s, since both are seen as scarce stores of value).

Speculative and Narrative-Driven Valuation: In practice, a lot of crypto valuation boils down to narratives (e.g., “Bitcoin is digital gold, so if it captures X% of gold’s market, it should be $Y”) or even pure momentum and sentiment. This is obviously not a rigorous fundamental approach, but it does describe how many market participants behave.

The key point is, there is no generally accepted valuation model for most digital assets.

Even something like Ether, which does have a quasi-“cash flow” in the form of network fees (some of which are burned under Ethereum’s tokenomics), doesn’t lend itself to a standard DCF easily because demand for blockspace is speculative and growth is uncertain.

This means analysts face high uncertainty in pricing and estimating fair value. Prices can diverge widely from any model’s estimates for prolonged periods.

In investment categorization terms, we’d say digital assets are “speculative assets” (value primarily dependent on what someone else will pay) rather than “investment assets” with clear intrinsic value. That doesn’t mean they are worthless – it just means valuation is based on unique factors (utility, scarcity, adoption, etc.) and likely to be volatile.

As one training slide succinctly put it: most cryptos “lack intrinsic cash flows, making traditional valuation models unsuitable”.

Investors must therefore rely on alternative metrics and be comfortable with a wide range of plausible values.

High Volatility and Return Profiles

Perhaps the most striking feature of digital assets is their extreme price volatility. By almost any measure, cryptocurrencies rank among the most volatile asset classes in history.

Annualized standard deviations of returns for Bitcoin have often been 60–100%, several times that of equities or gold.

For example, as of early 2024, Bitcoin’s volatility was roughly 47% annualized, compared to around 10% for global equities and 12% for gold.

In plain terms, these assets can swing in price by double-digit percentages in a single day – moves that would be considered extraordinary for stocks or currencies happen routinely in crypto markets.

Historical context: Bitcoin has experienced multiple drawdowns exceeding 70-80% of its value (after big bull runs in 2011, 2014, 2018, 2022).

These boom-and-bust cycles are far more severe than typical equity bear markets. Even Ethereum, the second-largest crypto, fell ~94% peak-to-trough in the 2018 crash, and again over 80% in 2022. Smaller altcoins often see even greater volatility, sometimes effectively going to zero if a project fails.

The returns, when positive, have been outsized as well. Bitcoin’s price famously went from under $1 in 2010 to over $60,000 in 2021 – an unmatched compound return (albeit with massive interim swings).

In certain periods, crypto returns have dwarfed other asset classes; but timing is everything, and late entrants in euphoria phases have suffered large losses.

Statistically, return distributions for digital assets have exhibited significant skewness and kurtosis – meaning large outlier moves (fat tails) are much more common than a normal distribution would predict.

This “non-normal” behavior challenges risk management, as standard deviation may underestimate the probability of extreme moves. Statistically we would say that crypto returns are non-normal — they exhibit skewness, kurtosis, and sharp drawdowns.

Why are digital assets so volatile? Several reasons:

Uncertain Valuation Anchors: As discussed, with no agreed intrinsic value, prices are driven by sentiment, momentum, and narratives. When the crowd is optimistic (e.g., believing crypto will revolutionize finance), money floods in and prices overshoot; when fear sets in (e.g., after hacks or regulatory crackdowns), there are few fundamental “floors” and prices can collapse until speculators see value.

Investor Composition: The crypto market historically has had a large retail investor presence and is driven by speculative trading. The presence of leverage (on unregulated exchanges, some traders use high leverage) and derivatives can amplify moves. Behavioral biases and herd behavior are strong – “momentum and narrative-driven behavior (news, hype cycles) influence returns”. These markets are also relatively young, without the stabilizing influence of decades-long institutional capital (though that is slowly changing).

Market Structure and Liquidity: While the largest cryptocurrencies have decent liquidity, the market overall can be fragmented among dozens of exchanges (with varying reliability). During stress, liquidity can dry up or fragment further, leading to gapping prices. Unlike equity markets, crypto trades 24/7 worldwide with no “circuit breakers,” so continuous trading can lead to exaggerated moves at odd hours. Furthermore, some exchanges have faced outages during volatile times, and the absence of market-making safeguards can yield bigger swings.

Unique Risks: Digital assets face some risks (discussed later) like hacking or protocol failures that can cause sudden repricing if they materialize. For example, a major exchange hack or a bug in a smart contract platform can trigger an immediate market sell-off that’s hard to predict via normal macro analysis.

Volatility cuts both ways – it means high risk, but also the potential (not promise) of high returns. Investors considering digital assets must be prepared for extreme drawdowns and rapid swings. Risk management (position sizing, possibly using stop-losses, etc.) is crucial if one is to hold these in a portfolio. Many advise that only a small allocation (that one can afford to lose) is prudent, precisely because of the volatility.

It’s also important to note that volatility has moderated somewhat as the market matured – Bitcoin in 2023 was less volatile than in 2013 – and major cryptos are even becoming less volatile than some speculative tech stocks. One study noted Bitcoin’s volatility had dropped such that it was “less volatile than 33 S&P 500 stocks” by late 2023. However, it remains much more volatile than broad equity indices or commodities. And smaller tokens still experience wild fluctuations.

Bottom line: Digital assets offer extraordinary return potential but with extraordinary volatility. This risk-return profile is unconventional – huge booms and busts – requiring a strong stomach and careful risk control.

As an investor or analyst, one should treat these assets as high-risk, speculative positions and calibrate expectations accordingly.

Liquidity and Market Depth

Liquidity in digital asset markets varies dramatically by asset. The top two assets – Bitcoin and Ether – are relatively liquid, with massive daily trading volumes across numerous exchanges. An investor can generally buy or sell large amounts of BTC or ETH (say, $10 million worth) without too much slippage in normal market conditions.

Moreover, the advent of regulated futures (e.g., CME Bitcoin futures since 2017) and exchange-traded products in some countries has further bolstered liquidity for the majors.

However, many altcoins are thinly traded.

There are thousands of tokens with small market capitalizations and low volume. Attempting to buy or sell a large position in those could move the market significantly. Slippage and execution risk are real concerns outside the top tier.

Liquidity depends on factors like whether the token is listed on major exchanges, how large its community is, and current market sentiment. In times of panic, even relatively larger altcoins can see liquidity evaporate.

Unlike equities, where market makers and exchanges maintain some orderly function, in crypto there is less structure – liquidity is purely supply/demand-driven and can be quite fickle.

Exchanges and trading venues: Liquidity is also segmented by venue. Crypto can be traded on centralized exchanges (CEXs) like Coinbase, Binance, Kraken, etc., or on decentralized exchanges (DEXs) like Uniswap (where users trade directly from wallets via smart contracts). Each exchange might have its own order book.

While arbitrage usually keeps prices in line, temporary dislocations happen.

Also, some large global exchanges have historically allowed extremely high leverage and hosted speculative activity that can cause short-term price anomalies (sometimes known as “long/short squeezes”). Traders need to be aware of which venues have reliable liquidity for the asset they are dealing with.

Trading hours: The crypto market never sleeps – it’s 24/7, year-round. This constant trading means events can trigger moves at any time, and there isn’t a concept of “market close” to pause and digest news (which can both exacerbate volatility and allow faster price discovery in some cases).

From a CFA exam perspective, one should appreciate that liquidity risk is part of digital asset investing.

A small-cap token might look good on paper but could be difficult to exit without impact cost. Conversely, Bitcoin’s liquidity has reached levels where it’s easier to trade than many emerging market stocks.

Indeed, Bitcoin’s daily trading volumes often exceed those of major stock indices. But even Bitcoin can have liquidity crunches during extreme volatility – e.g., if exchange outages occur or if large holders all rush for the exits simultaneously.

In summary: not all digital assets are equal in liquidity.

The majors are liquid (though still not as deep as, say, FX markets), whereas many others are not. Liquidity considerations should influence position sizing and choice of investment vehicle. (For example, one might prefer a Bitcoin ETF or future for easier exposure, rather than buying directly and dealing with custody – more on vehicles later.)

An analyst should check trading volumes and exchange listings when evaluating a digital asset’s liquidity.

Market Efficiency and Information Flow

Are crypto markets efficient?

This is an open question. On one hand, the existence of many retail participants, frequent bouts of irrational exuberance or fear, and fragmented markets suggests inefficiencies – i.e. opportunities for arbitrage or alpha from superior analysis.

There have been instances of price anomalies: for example, at times a coin trades at different prices on different exchanges (leading to arbitrage opportunities), or patterns like the “Kimchi premium” in 2017 where Bitcoin traded significantly higher in South Korea than elsewhere due to local demand. These indicate friction and segmentation.

Academic studies have found evidence of momentum and other factor effects in crypto. The absence of long-standing institutional players early on meant fewer algorithmic trading strategies to arbitrage away things like momentum or seasonality. This created a somewhat Wild West environment where sharp traders could profit from others’ behavioral biases.

On the other hand, crypto markets are extremely competitive and fast-moving.

Because they’re open 24/7 and globally accessible, any new information (say, a regulatory announcement or a hack of a protocol) gets quickly reflected in prices around the world. Arbitrage opportunities, while they appear, often get closed by savvy traders or bots quickly.

The rise of high-frequency trading and sophisticated funds in crypto (including many with Wall Street experience) is increasing efficiency over time. Compared to five years ago, today’s crypto market has tighter spreads on major assets and more derivative instruments enabling arbitrage (e.g., between futures and spot).

An interesting aspect is informational opacity: valuable information in crypto might come from unusual sources – developer chats, governance forum discussions, on-chain analytics (monitoring blockchain data for large movements or smart contract activity) – rather than traditional financial disclosures.

Those who know where to look on-chain can detect trends (like big holders moving coins, or smart contract exploits in progress) before the broader market reacts. This creates a different kind of informational edge than in equity markets (where everyone watches earnings reports and economic indicators).

The crypto markets are still relatively inefficient compared to traditional ones. Prices may also reflect herd behavior, sentiment, or limited arbitrage opportunities, rather than pure fundamentals.

It also notes there’s “no definitive evidence of persistent alpha opportunities, but inefficiencies persist”.

In plainer terms: we suspect there are trading opportunities due to inefficiencies, but it’s a very risky game and not guaranteed.

From an exam lens, it’s safe to say digital asset markets are less mature and possibly less efficient than major stock or bond markets. They can exhibit bubbles and crashes untethered to fundamentals (to the extent fundamentals exist).

Behavioral factors like fear of missing out (FOMO) or panic selling often dominate rational valuation. However, as the market matures, efficiency appears to be improving – especially for the large-cap digital assets which now have many professional traders and quant funds active.

Correlation with Traditional Assets and Diversification Potential

A critical question for portfolio management is how digital assets correlate with stocks, bonds, and other assets.

Initially, cryptocurrencies were touted as having low or even zero correlation with traditional asset classes – meaning they could provide significant diversification benefits. Indeed, in the early years, Bitcoin’s correlation with equities or gold was often near zero (or even slightly negative at times).

This made sense because crypto was largely isolated – driven by idiosyncratic factors unrelated to the broader economy.

For example, prior to 2020, one could find periods where Bitcoin’s price movements bore little relationship to stock market moves. During some stock market corrections, Bitcoin did its own thing. Low correlation means adding a small allocation of crypto could, in theory, improve a portfolio’s risk-adjusted returns (because its ups and downs would offset or be unrelated to the rest of the portfolio).

However, an important observation in recent years: as crypto adoption grew and more traditional investors entered the space, correlations have risen.

Particularly post-2020, Bitcoin and other major cryptos started moving more in tandem with risk assets. The COVID-19 pandemic was a turning point – when global markets crashed in March 2020, Bitcoin also crashed (over 50% in a day), showing it was not a safe haven in that crisis. Subsequently, the huge stimulus and low-rate environment fueled both a stock rally (especially tech stocks) and a crypto rally in 2020-2021.

The result was crypto behaving like a high-beta risk asset: when stocks go up, crypto often goes up more; when stocks fall, crypto can fall more. In other words, correlations, especially with equities (particularly tech), have become positive in many periods.

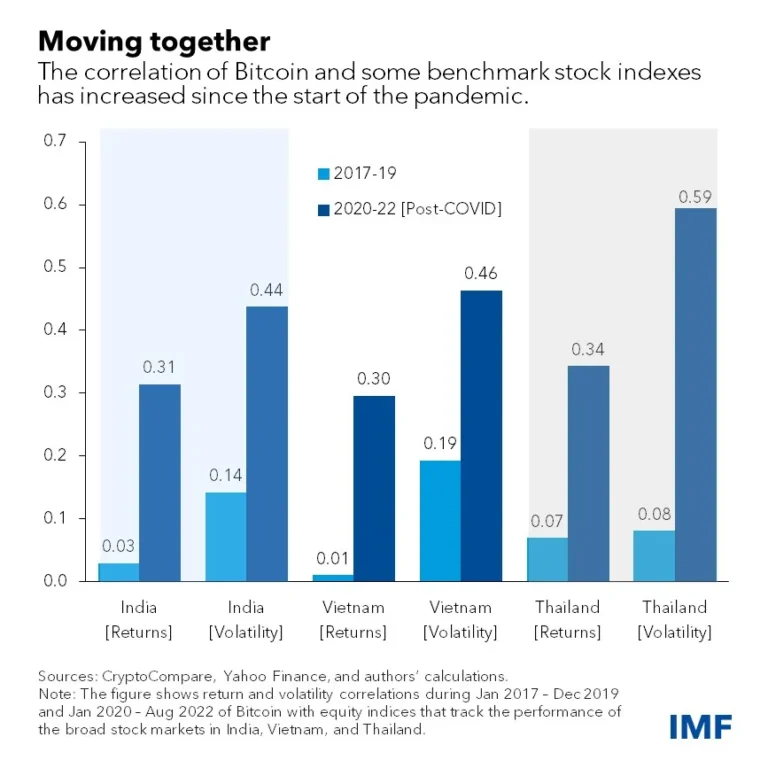

The IMF noted that before the pandemic, crypto was fairly insulated from the financial system, but “the correlation between Bitcoin and stock markets increased 10-fold during the pandemic,” diminishing diversification benefits. They found return correlations between Bitcoin and some Asian equity markets jumped from near 0 to 0.3–0.5, and volatility correlations (how volatility in one market coincides with volatility in another) also spiked.

The chart below illustrates this shift:

Correlation of Bitcoin with stock indexes (2017-2019 vs 2020-2022). Bitcoin’s correlation with equities has increased significantly in the post-2020 period, indicating that during market stress or broad rallies, crypto and stock prices have tended to move together more closely. This rising correlation suggests that the diversification benefit of adding crypto to a portfolio, while still present, may be conditional and not as large as it once was.

As shown above, in markets like India, Vietnam, and Thailand, Bitcoin’s return correlation went from virtually zero pre-2020 to as high as 0.3 or more post-2020, and volatility correlation jumped even more (for Thailand’s market, volatility correlation reached 0.59 post-COVID, up from 0.08 pre-COVID).

This indicates that when there’s a volatility event affecting stocks, it now often affects crypto similarly – likely due to global risk sentiment.

However, it’s not all one-way. There are still periods and regimes where crypto’s correlation dips. For instance, in times of crypto-specific bull markets (like 2021’s NFT boom) or crypto-specific crises (like a big exchange collapse) the correlation with equities can decouple somewhat.

Also, crypto is still uncorrelated with bonds for the most part, and with some other assets like commodities there isn’t a clear pattern.

From a portfolio perspective, many analyses (including those by asset managers) have shown that a small allocation to Bitcoin historically could improve portfolio Sharpe ratios due to its high returns and previously low correlations.

For example, a study by VanEck in 2024 found that adding up to 6% in Bitcoin/Ether to a 60/40 stock-bond portfolio “substantially enhanced the Sharpe ratio with only a minor impact on drawdown”.

Even for risk-tolerant portfolios, they suggested up to 20% crypto could keep improving risk-adjusted returns, though with much higher volatility that only certain investors could tolerate. Meanwhile, a more conservative analysis by others might say even a 1-2% allocation can be beneficial, but going beyond say 5% starts to dominate portfolio risk too much.

The diversification benefit is real but likely diminishing as crypto integrates with mainstream finance. Importantly, correlations tend to increase during market crises – a phenomenon seen across many asset classes (e.g., even gold sometimes sells off initially in a liquidity crunch as everything becomes correlated).

Crypto, being perceived as a “risk-on” asset, often sells off when there’s a flight to safety. Thus, one should not count on it as a hedge in tail risk scenarios (at least based on recent evidence). It seems to behave more like equities than like gold in panics.

To encapsulate: earlier, crypto had appealingly low correlations (making it a great diversifier on paper), but “correlation is not stable — it tends to increase in market stress periods”.

Going forward, if institutional adoption continues, crypto may continue correlating with other risk assets, especially tech/growth equities. On the flip side, crypto still has unique cycles and catalysts (like halving cycles for Bitcoin, technological upgrades) that can cause idiosyncratic performance.

For CFA candidates, it’s safe to say that a small allocation to digital assets could improve diversification and potentially returns, but one must handle it with nuance. The benefit is highly sensitive to the time period and the extreme volatility means rebalancing is crucial.

Moreover, one must be wary of assuming correlations will remain low in crises – evidence shows they rise when most needed. We’ll revisit portfolio allocation in a later section.

Other Notable Features: Market Access and 24/7 Trading

Before moving on, two other features to highlight:

Accessibility and Fractional Ownership: Digital assets can be bought in tiny fractions (you can purchase 0.0001 of a Bitcoin, for example). This fractional divisibility (Bitcoin is divisible into 100 million satoshis) means investors can start with very small dollar amounts, unlike some other investments that might have higher entry points. Combined with ease of access through online platforms and even mobile apps, this has democratized participation – for better or worse (some argue it enabled many unsophisticated investors to speculate and get hurt). Nonetheless, it’s a feature to note: nearly anyone with an internet connection can access crypto markets, which is not true of, say, buying foreign stocks or certain bonds.

No dividends or yield (except via crypto lending/DeFi): Most digital assets don’t inherently pay interest or dividends (they’re like gold in that sense – a non-yielding asset). However, in crypto, one can “put assets to work” in ways like staking (for PoS coins, staking Ether yields a protocol reward akin to interest) or lending out crypto on platforms (earning interest, albeit with risk). DeFi allows providing liquidity or lending to earn yield in crypto terms. These can generate returns but also add risk layers (platform risk, smart contract risk). The yield environment in DeFi can sometimes be very high (attracting many), but also can be unsustainable or involve hidden risks.

Overall, digital assets combine aspects of currencies, commodities, and speculative securities in their investment features. They are volatile, hard to value, heavily sentiment-driven, but also potentially useful for diversification and capable of outsized gains. The savvy investor must weigh these features carefully.

Next, we will discuss how one can invest in digital assets – the various investment vehicles and forms available – and then delve deeper into the risks to be mindful of when dealing with this asset class.

Investment Vehicles and Methods for Digital Asset Exposure

Investors can gain exposure to digital assets in multiple ways. Broadly, one can either invest directly (holding the digital assets themselves) or indirectly (through financial products or vehicles that reference digital assets).

Each approach comes with different considerations for accessibility, custody, regulation, and risk.

Here we outline the main forms and vehicles for digital asset investment, from owning tokens outright to using exchange-traded funds, futures, and even public company stocks that provide crypto exposure.

We’ll also cover key infrastructure aspects like wallets and custody solutions, and the evolving regulatory landscape around these investment forms.

Direct Investment: Owning Digital Assets Outright

The most straightforward way to invest is to buy the digital tokens directly – for example, purchasing Bitcoin or Ether and holding it in your own wallet.

This can be done via cryptocurrency exchanges (like Coinbase, Binance, Kraken, etc.), brokerage apps that offer crypto, or even peer-to-peer transactions. When you buy directly:

You own the actual asset. This means you can use it as you wish – not just for investment, but potentially to transact or participate in network activities (like using ETH to interact with DeFi). You have full exposure to its price movements.

Ownership is represented by control of private keys. A private key is like a secret password that allows you to access and transfer your crypto on the blockchain. If you hold your own keys (say, in a personal wallet), you truly self-custody the asset. If you keep the asset on an exchange, the exchange holds the keys for you (custody on your behalf, somewhat analogous to a bank).

Full exposure, full responsibility: Direct ownership comes with certain risks: if you lose your private key or seed phrase (and have no backup), your assets are gone forever – there is no hotline to reverse a transaction or reset a password in a decentralized system. If your computer or wallet is compromised by hackers, your funds can be stolen. Also, sending assets requires caution; an irreversible mistake (sending to the wrong address) can be costly.

Despite those challenges, many crypto enthusiasts favor direct investment as it embodies the ethos of decentralization (“be your own bank”). Even for investors, direct ownership avoids intermediary fees on ongoing management (though you might pay a trading fee upfront) and gives you the flexibility to move your assets or utilize them in ways a fund might not allow.

From a CFA exam perspective: direct investment is like owning physical gold bars versus gold ETFs – you have the asset in hand (or rather, in wallet). As a result risks such as custody, hacking, regulatory uncertainty are borne by you.

Digital Wallets: If holding directly, one must use a digital wallet. Wallets come in different forms:

Hot wallets: Software (mobile or desktop apps, or web-based) that are connected to the internet. Examples include smartphone apps like Trust Wallet or MetaMask (browser extension). They are convenient for frequent use (trading, DeFi, etc.) but are more exposed to hacking (if your device has malware, or if the platform has a vulnerability).

Cold wallets: Offline storage, such as hardware wallets (physical devices like a Ledger or Trezor) or even paper wallets (simply writing down your private key/seed and not keeping it on a computer). Cold wallets are considered the safest for long-term storage because they are not exposed to online threats when kept offline. For instance, a Ledger hardware wallet stores your keys and signs transactions internally… even if connected to a malware-infected computer, the design prevents the key from being exposed. The trade-off is convenience – accessing your funds requires the device, and transactions are a bit slower to initiate.

Custodial wallets: If you keep crypto on an exchange or use certain wallet services, you might not hold the keys yourself; the provider does. This is easier (you just log in with a username/password), but then you rely on that provider’s security and honesty. The mantra in crypto circles is “not your keys, not your coins.” Custodial solutions can range from exchanges to specialized custodians that offer institutional-grade storage (with multi-signature setups, insured vaults, etc., often used by funds and ETFs).

In summary, direct investment is viable for those comfortable with the technological aspect and wanting unmediated exposure.

For many retail investors, using a reputable exchange and maybe a hardware wallet strikes a balance between ease and security.

Indirect Investment: Funds and Exchange-Traded Products (ETPs)

As crypto gained popularity, traditional financial products emerged to provide exposure without requiring investors to handle the assets directly.

These include exchange-traded products (ETPs) like trusts or ETFs, as well as closed-end funds. The idea is similar to buying gold via an ETF like GLD instead of holding bullion.

Exchange-Traded Funds / Products: Several crypto ETPs now exist, especially outside the U.S. (in Canada, Europe, etc., regulators have approved Bitcoin or Ether ETFs). These trade on stock exchanges and track the price of the underlying crypto. For example, the Purpose Bitcoin ETF in Canada holds actual Bitcoin in custody and issues shares that trade on the Toronto Stock Exchange. Investors can buy those shares through their regular brokerage – gaining Bitcoin exposure in a traditional wrapper. In the U.S., fully backed spot Bitcoin ETFs were long delayed by the SEC (though futures-based ETFs have been allowed since 2021). By 2025, it’s anticipated that multiple jurisdictions will have both spot crypto ETFs (backed by actual holdings) and futures-based ETFs (holding futures contracts).

The advantages of ETPs: convenient access (no need for a crypto exchange account or wallet), integration into existing portfolios (you can hold them in retirement accounts, etc.), and regulatory oversight/ investor protections associated with securities. Also, you avoid having to manage keys or worry about personal theft – the fund’s custodian handles that (typically storing the crypto in secure cold storage). Liquidity can be good if the ETF is liquid, and transactions are as easy as trading any stock.

The downsides: fees (ETPs charge management fees, perhaps ~1% or more annually), and some risks like the product not perfectly tracking the price (especially futures ETFs can have tracking error due to rolling futures). Additionally, you can only trade during market hours (whereas crypto trades 24/7, though the ETF’s price will reflect after-hours moves when it opens). For long-term investors, these are minor issues relative to the convenience.

One distinction: Grantor trusts vs ETFs – e.g., the Grayscale Bitcoin Trust (GBTC) is a popular U.S. vehicle, but it’s not an ETF; it’s a trust that holds Bitcoin. It trades over-the-counter and sometimes at large premiums or discounts to NAV because creations/redemptions are restricted. True ETFs allow market makers to create/redeem shares to arbitrage the price to closely track NAV. So ETF is generally preferable for tracking accuracy. Both fall under the umbrella of ETPs in that they’re exchange-traded.

Closed-End Funds / Trusts: As mentioned, products like Grayscale’s trusts (Bitcoin, Ethereum, etc.) allowed early institutional exposure. They have quirks like lockup periods for creation and often trade at discount/premium. In some countries, there are listed funds that operate similarly. These are a bit less ideal than ETFs but have been widely used.

Mutual Funds: There are a few diversified funds or trusts that invest in baskets of digital assets or related companies. For example, some actively managed crypto funds accessible to retail (mostly outside U.S., or as private trusts in U.S.). These could hold multiple cryptos, providing some diversification within the asset class.

Indirect Investment: Futures, Options, and Structured Products

Investors comfortable with derivatives might use crypto futures and options. On regulated venues like the Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME), one can trade Bitcoin and Ether futures (which are cash-settled).

These allow hedging or speculation with leverage in a regulated environment. For instance, a futures contract on CME represents 5 BTC (for Bitcoin futures), enabling exposure without owning actual bitcoin.

Hedge funds or ETF providers often use these to gain exposure indirectly.

Advantages of futures/options:

~ They allow leverage and short exposure (important if one wants to bet against or hedge holdings).

~ They’re traded on an exchange with clearing, which mitigates counterparty risk relative to unregulated platforms.

~ They also have defined expiry and can be used in arbitrage strategies (like cash-and-carry trades exploiting price differences between futures and spot).

Disadvantages:

~ Futures require rolling if you want long-term exposure (which can incur costs if futures are in contango with higher forward prices).

~ They also need margin and careful management of leverage.

~ Options on Bitcoin/Ether (on CME or crypto platforms like Deribit) allow strategies like buying calls/puts or spreads to express views on volatility or protect downside.

For many institutional investors, derivatives are the preferred way to get limited exposure, given the comfort with those instruments and not needing to handle custody of coins.

Also, banks and fintech companies have started offering structured notes or certificates tied to crypto performance for clients. For example, a note might pay a coupon linked to Bitcoin’s price or principal protection with upside capped, etc.

These are bespoke and not common for most retail, but they exist in the market.

Futures and options are a key avenue that allows exposure with leverage and hedging strategies, but require understanding of margin, volatility, and liquidity risks. Essentially, they are powerful tools for those who know how to use them, but not recommended for novices due to complexity and risk.

Indirect Investment: Public Equities and Crypto-Themed Companies

Another way to get indirect exposure is via investing in companies that are involved in digital assets.

Some examples:

Crypto miners: These are companies (often publicly listed now) that operate cryptocurrency mining hardware, validating transactions and earning rewards (primarily for Bitcoin). Examples include Marathon Digital Holdings or Riot Platforms in the U.S., which mine Bitcoin. Their stock prices tend to be highly correlated with Bitcoin’s price – often leveraged, as their profits amplify Bitcoin moves (and because they may hold some Bitcoin on their balance sheet). So investors might buy a miner stock as a proxy for Bitcoin exposure.

Exchange or Broker stocks: Coinbase, a major crypto exchange, is publicly listed (COIN). Its performance ties to crypto market volumes and interest (it benefits from high trading activity and prices, and suffers in downturns). Other public companies like Robinhood have some crypto business component.

Companies holding crypto: Perhaps the most famous is MicroStrategy (MSTR), a software company that turned its treasury into a massive Bitcoin position (owning over 100,000 BTC). Its stock now trades almost like a Bitcoin ETF, moving with BTC due to its holding. Tesla also bought Bitcoin (though only a small portion of its huge market cap). If a company holds significant crypto, buying its stock is a backdoor way to get crypto exposure (albeit with other business influences).

Blockchain technology companies: For a broader theme, some companies focus on blockchain development, enterprise DLT solutions, or hardware (like companies making mining chips). However, these often have diversified businesses (e.g., Nvidia sells GPUs used in mining but also for many other things).

The caveat: investing in a company for crypto exposure adds layers. You get indirect exposure diluted by other business aspects. For instance, Coinbase’s stock could drop due to regulatory concerns or lower trading fees even if Bitcoin’s price is stable – so it’s not a pure proxy.

Also, equities are subject to equity market sentiment – in a risk-off, even if Bitcoin is flat, an equity like MicroStrategy might fall due to general market concerns. Thus, correlation might not be one-to-one.

But for some investors or funds not allowed to buy crypto directly, these equities were historically one of the only ways to play the theme.

It’s similar to how some invest in gold miners as a leveraged gold play, instead of or in addition to gold itself.

Private Investment Vehicles (Funds, VC, Hedge Funds)

For more sophisticated or accredited investors, private funds focused on digital assets are an option:

Crypto Hedge Funds: These are actively managed funds (usually open only to qualified purchasers, etc.) that trade or invest in digital assets. Strategies can range: some are long-only investors, others quantitative traders or arbitrageurs, others multi-strategy including DeFi yield farming, etc. They often charge the typical hedge fund fees (2% management, 20% performance or similar). The advantage is professional management and possibly access to strategies retail might not easily do (like arbitrage between exchanges, early-stage token investments, etc.). The disadvantage is high fees, lock-ups or limited liquidity, and reliance on manager skill (and operational risk of the fund).

Venture Capital / Private Equity in blockchain startups: Many VCs invest in early-stage crypto companies or protocols (sometimes receiving tokens or equity). For example, a16z (Andreessen Horowitz) has large crypto funds. These are long-term investments with high risk and potential high return, not liquid until maybe the startup exits or tokens unlock. They’re akin to tech startup investing, but in the blockchain realm.

Private trusts or lending funds: Some firms offer interest-bearing crypto products, where you lend out your crypto to earn yield (though the 2022 failures of some lending platforms like Celsius and BlockFi highlight the risks of that approach – those were not exactly funds but offered yield and collapsed due to risky lending practices).

Private vehicles are accessible only to accredited / institutional investors, but they have been proliferating. They can offer exposure beyond just holding Bitcoin – e.g. diversified baskets, actively trading to outperform the market, or thematic focus like metaverse, NFTs, etc.

Due diligence is extremely important, as these operate in a less regulated space and one is trusting the fund managers with potentially opaque assets.

Interested in Learning About Other Hedge Fund Strategies?

Custody Solutions and Security Considerations

When investing in digital assets, custody is a key consideration – how and where are the assets stored? If investing indirectly through an ETF or a custodian, one should evaluate the custodian’s security. If directly, one must choose how to custody oneself (as discussed with wallets).

For institutions, a whole industry of crypto custodians has emerged. These firms (like Coinbase Custody, Fidelity Digital Assets, BitGo, etc.) offer secure storage with multi-signature controls, insurance coverage, auditing, and compliance – aiming to meet institutional standards.

Many require regulatory approvals (some are licensed trusts or equivalent). Big custodians might use “air-gapped” vaults, geographically distributed keys, and other measures. The idea is to minimize the risk of theft or loss. Institutional investors typically require a qualified custodian by regulations (for example, mutual funds need one), so these services are critical for broader adoption.

Insurance: Some custodians carry insurance for digital asset theft, but it’s often limited (there are not many insurers who cover full cold storage risk beyond certain amounts). It’s an evolving area.

Regulation of custody: Regulators have been looking at how to integrate crypto custody into existing frameworks. Some jurisdictions now have licenses for crypto custodians similar to securities custodians.

Regulation of Digital Asset Investments

Finally, one must consider the regulatory environment, which varies widely by product and by country.

A few key points:

Direct ownership of tokens might be lightly regulated in some places (e.g., in many countries, simply buying/selling crypto is allowed but not specifically regulated, though anti-money laundering (AML) rules apply via exchanges). However, some countries ban or restrict it (China banned crypto trading and mining in 2021… other countries disallow banks from touching crypto, etc.). So an investor must ensure it’s legal and know tax implications (tax authorities generally treat crypto trades as taxable events akin to property trades).

ETPs and funds usually fall under securities laws. So a crypto ETF in Europe is regulated like any ETF, requiring disclosures, etc. The availability of such funds depends on regulators’ stances. In the US, the SEC’s reluctance to approve spot Bitcoin ETFs was a major story, but they did allow futures ETFs under the Investment Company Act.

Derivatives might be regulated by commodities regulators (e.g., CFTC in the US oversees Bitcoin futures as a commodity). Unregulated exchanges offering derivatives (like many offshore platforms) fall in a gray area and have been targeted by enforcement actions for allowing US customers, etc.

Securities law and tokens: A big area of regulatory focus is whether certain tokens are considered securities (and thus should have been registered, comply with investor protection rules, etc.). The U.S. SEC has pursued cases arguing some ICO tokens were unregistered securities. The legal classification can impact whether exchanges can list them, what reporting is needed, etc. This uncertainty is a risk – e.g., if a major token is suddenly deemed a security, it could be delisted from many platforms not licensed to trade securities.

Investor protection: Regulators worry about fraud (there have been many scams and Ponzi schemes in crypto), market manipulation (thin markets can be manipulated; stablecoins raise concerns of manipulation of crypto prices too). So frameworks are slowly being built. For instance, the EU’s MiCA (Markets in Crypto-Assets) regulation (approved in 2023) is a comprehensive regime for crypto asset issuance and service providers, aiming for consumer protection and market integrity.

Regulatory arbitrage: Different countries range from crypto-friendly (some even making Bitcoin legal tender like El Salvador) to crypto-hostile (bans in China, etc.). Some investors choose jurisdictions or exchanges accordingly, but that can pose additional legal risk if rules change.

The upshot is regulatory clarity is evolving and critical. An investor should stay abreast of their jurisdiction’s rules about holding or trading digital assets and the status of any investment product.

Regulation can also significantly impact market sentiment. For example, a positive development like the approval of a Bitcoin ETF in the U.S. might spur price rallies, whereas a negative like an outright ban in a large economy can trigger sell-offs.

Having covered the ways to invest and the infrastructure around it, we move next to a critical analysis of risks associated with digital asset investments.

Many have been hinted at already, but we will systematically go through the risk factors – beyond just volatility – that investors should understand.

Risks of Investing in Digital Assets

Any investment comes with risks, but digital assets carry some unique and heightened risks that warrant careful consideration. Some of these are linked to their technological nature, others to immature market infrastructure or evolving regulation.

In this section, we analyze the major risk categories: market risk and extreme volatility, regulatory and legal risk, technological and cybersecurity risk, operational and custody risk, and fraud/manipulation risk. Understanding these will help in making informed decisions and implementing proper risk management when dealing with crypto assets.

Market Risk and Extreme Volatility

We’ve already discussed price volatility in the features section, but to frame it as a risk: digital assets can experience severe price swings and drawdowns that exceed those of most asset classes.

This is the primary market risk – the potential for large losses in market value. An investor in Bitcoin must be mentally and financially prepared for it to drop 50%+ within months (or even days, in freak events). Such moves can trigger panic selling, margin calls (if leveraged), and emotional decision-making that locks in losses.

Drawdown risk is very high. For instance, if you bought Bitcoin at its peak in late 2021 (~$69k) and held through 2022, you would have seen it fall to around $20k (a drop of ~70%). Recoveries can take a long time, if they happen at all – those who bought the peak of 2017 had to wait 3+ years to break even. Many smaller tokens never recover after a crash, especially if tied to a fad (like numerous ICO tokens from 2017 that went to zero).

This risk is compounded by liquidity crunches in downturns – if everyone rushes for the exit, the inability to sell at a “fair” price is a risk. Though for top assets like Bitcoin, some buyers (value investors or institutional) might step in as they see long-term value, so liquidity is relative.

Managing market risk: traditional tools like diversification help somewhat (though as discussed, in a portfolio crypto might amplify risk if overweight). Other tools include stop-loss orders, options hedging (e.g., buying put options for downside protection), or position sizing (only allocate what you can afford to lose). However, stop-losses on an exchange may not guarantee a price if the market gaps, and options may be costly (implied volatilities are high). Realistically, many crypto investors ride out volatility with a long-term conviction or use strategies like dollar-cost averaging to mitigate timing risk.

From a risk perspective, one should also consider macro sensitivities: as crypto has become more tied to macro conditions (liquidity, rates), it is susceptible to changes in the economic environment. For instance, rising interest rates in 2022 were cited as a factor in crypto’s bear market (less easy money to speculate). So there’s an emerging macro risk element: if risk assets in general are out of favor, crypto likely will be too.

In essence, market risk for digital assets is extremely high, and an investor should size positions accordingly and be ready for high volatility. Scenarios for stress tests could include an 80% price drop, which is something few other assets would realistically face in normal conditions, but is plausible in crypto.

Regulatory and Legal Risk

Regulatory risk is one of the most significant uncertainties hanging over digital assets. Governments and regulators worldwide are still grappling with how to treat crypto, leading to rule changes or enforcement actions that can materially impact the market.

Some aspects of regulatory risk:

Bans or Restrictions: A government could outright ban cryptocurrency trading, mining, or usage, which would immediately affect demand and possibly cause prices to plummet in that jurisdiction (and globally, due to sentiment). The extreme example was China’s ban in 2021, which caused miners to relocate and temporarily depressed the market. Other countries like Turkey and Nigeria have placed restrictions on use or banking support. Even talk of bans (e.g., potential ban of proof-of-work mining in some regions over environmental concerns) creates uncertainty.

Securities Law Enforcement: As mentioned, regulators like the SEC are scrutinizing whether tokens are unregistered securities. If major tokens (besides obvious ones like Bitcoin which is generally seen as a commodity) are declared securities, exchanges not registered as securities brokers might delist them, causing liquidity to vanish and prices to drop. There have been lawsuits (e.g., SEC vs Ripple about XRP token) that create legal risk for holders of those tokens pending outcomes.

Tax Treatment: Unfavorable tax changes can deter investment. Many countries tax crypto similar to property – triggering capital gains on each sale or even each time crypto is used to buy something (which is cumbersome). Some might implement high taxes on trading or mining. Lack of clarity can itself be a risk (people might accidentally violate tax rules).

AML/KYC and Policing Crime: Because crypto can be used pseudonymously, regulators worry about money laundering, terrorist financing, etc. This has led to strict compliance requirements for exchanges (KYC every user) and travel rule compliance (exchanges sharing info on transfers above certain amounts). While necessary for law enforcement, it adds friction and could push some activity underground or away from regulated venues.

Regulating DeFi and stablecoins: Newer areas like DeFi (decentralized exchanges, lending, etc.) present a regulatory challenge – there’s no obvious entity to hold accountable. Regulators may find ways (e.g., going after the developers or front-ends or those in jurisdiction). Stablecoins are under heavy scrutiny, as they intersect with the traditional monetary system. For instance, there could be rules requiring issuers to be banks or to hold certain reserves (which could impact which stablecoins survive or their costs).

Jurisdictional Arbitrage: The global nature means if one country cracks down, activity might shift elsewhere (as China’s mining ban saw hashrate move to the US and Kazakhstan, for example). But for an investor, being caught in a crackdown can be painful (assets frozen, loss of access, or needing to move assets quickly).

Legal risk also includes the contractual and rights issues: for instance, if you hold coins on an exchange that goes bankrupt, legal battles may determine if those are your property or part of the bankruptcy estate (as seen in some bankruptcies like Mt. Gox ormFTX – customers become unsecured creditors). The lack of SIPC-like insurance for exchange accounts is a risk.

Additionally, as new laws come, existing holdings might be grandfathered in awkward ways or face compliance burdens. For example, the U.S. infrastructure bill of 2021 included broad language possibly requiring tax reporting from even miners or wallet providers – causing an outcry; if enforced as written, it would be problematic.

For large investors, regulatory uncertainty can limit involvement. Many institutions held back on direct crypto exposure for years mainly due to unclear regulation and fear of later repercussions (like custody rules, accounting treatment, etc.). This in itself is a risk: if regulation remains uncertain, some potential demand stays sidelined; conversely, if regulations become clear and reasonable, more investors may come (a sort of regulatory “risk” on the upside if clarity boosts adoption, or downside if clarity is very restrictive).

To sum up, regulatory risk is rapidly evolving and region-specifics. It can significantly affect the viability and price of digital assets. Investors must monitor regulatory developments closely and adapt. It’s wise to assume that compliance costs will rise and some current practices (like certain DeFi yields or privacy coins) might face clampdowns.

Technological and Cybersecurity Risk

Technological risk is inherent to digital assets because they are, fundamentally, lines of code running on software networks.

There are several dimensions to this risk:

Smart Contract Bugs and Failures: Many digital assets (particularly tokens on platforms like Ethereum, or DeFi protocols) rely on smart contracts – code that automates transactions and rules. If there’s a bug in a smart contract, it can be exploited by attackers to steal funds or otherwise not perform as intended. There have been numerous instances of hacks due to coding errors. For example, in 2016 the DAO (a decentralized venture fund on Ethereum) was hacked due to a smart contract flaw, leading to a theft of ~$60 million ETH and eventually a hard fork of Ethereum to recover it. More recently, DeFi platforms have been hacked for hundreds of millions by exploiting vulnerabilities. If you invest in a token or project that suffers such a bug, the value can plummet or go to zero quickly. Unlike traditional finance where legal agreements might offer recourse, in blockchain “code is law” – if the code fails, your recourse is limited (unless the community forks the chain or such, which is rare).